Challenges of methodological procedure

This article serves as an exercise in how to consolidate argument for methodological process in a context of developmental phenomenography. It is a work in progress, being edited currently. Itâs based on 13k words of draft âthinkingâ, most of which will not be included in the thesis final version. That might, if itâs lucky, form some basis for papers that discuss these kinds of challenges. But this summary is vital for my understanding of how to write about this stuff in a coherent non-flabby way.

Background

I have been challenged recently by complex issues regarding the nature of the project and the requirements of the procedure necessitated by it. The problem has been whether or not Iâm âgoing againstâ received wisdom of usual methods/process for phenomenographic studies, or proceeding as the project best benefits from. Iâve attempted to create a clear perspective by writing â to teach myself what the literature says and to try to find a way through the maze of phenomenographic precedent. I needed to argue out what Iâm doing (investigating) and why Iâm doing it that way (methods and procedure). 13k words later on phenomenographic context of responsive conversational partnership interviews, bracketing, delimiting explicit aspects of the interview, iterating analysis perspective lenses and interpretations, and things did not feel much clearer. To make it worse, Iâm still negotiating the stress of only having half my data at this late stage, so these theoretical framework issues for the core methodology are therefore feeling very acute.

Last week I think I finally made a small mental breakthrough which I *hope* might help to clear my mind. After continual reflection and re-reading what Iâd written several times, I realised I needed to fully establish what it is Iâm investigating.

What is being examined?

The fundamental question to ask is:

Am I examining learners conceptions of a smart learning activity, or am I examining learners experiences of aspects of a smart learning activity?

By acknowledging Iâm setting out to do a lot of the latter and somewhat of the former as a consequence of the latter, I may be able to forge a good position.

- My âdelimited elementsâ of the smart learning activity interview are interpreted in a first iteration of analysis by taking all utterances â from all four delimited elements (these being place, knowledge, collaboration and technology) â as a whole, examining structure of awareness variation, to form overall categories of conception of a smart learning activity, at collective level. A system for doing this is being developed (after Edwards, 2005, and Cope, 2004)

- As a second iteration, each delimited element can potentially be analysed in some way1 within itself to see how variation and commonality of experience is formed at collective level for each element. This would ideally take the first iteration findings and âreshuffleâ into the delimited areas, if this is possible.

- Thirdly, analysis looks at âpedagogical aspects of interestâ using a level of presence and complexity âscoreâ, again after Edwards, 2005. Other phenomenographers (Bruce, 1994? Not referenced) who use a level of complexity scale need to be investigated. This can derive possible categories of variation for pedagogical aspects of interest. This iteration also benefits from a triangulation with a Bloomâs/SOLO measurement for any digital content generated by learners in the learning activity event (see current thesis chapter 3 tables.)

- A final iteration can then âscoop upâ each small cohort group and their specific smart learning activity event, to look at a âmicro-poolâ of meaning that might be found in that context.

I am examining experiences of an actual event and the parts of it, and in consequence potentially discovering overarching âconceptionsâ in both general and âhypotheticalâ contexts, after Ă kerlind, 2005b, p. 66, or SĂ€ljöâs (1979) example questions. From this position I may be able to establish clarity and evidenced reasoning â the justification â for how I am going about it.

Summary of relevant issues

Key thoughts in summary, that will permit much more concise argument to be formulated, are:

- Itâs an actual event that learners are recalling â the smart learning journey they participated in (or not). - To examine a past actual event (rather than overarching âconceptionsâ), aspects of a method known as the âelicitation interview techniqueâ (EIT) have been employed.

- EIT has been combined with phenomenographic analysis before (Jarrett & Light, 2018).

- EIT is used in HCI and usability in recent years (Hogan et al., 2016), attempting to gather more useful user data, what they âexperienceâ rather than just what they âdoâ.

- Iâm using some of that technique in relation to aspects of the past event, probing these aspects for their experiential reflections. But, Iâm not using the specific form of elicitation interview technique. (EIT is basically creating an illusion of a think aloud âpresent tense reflectionâ from an interviewee, of a specific past event they experienced.)- Jarrett et al (2014), argue that maintaining the present tense is difficult: âdiscussion within interviews was more âactivity descriptionâ than âactivity relivingâ'(p. 301) in EIT. Perhaps this chimes with the phenomenographic âEIT influencedâ responsive technique I feel I have employed. This permits the âhowâ (the structural act of learning) to then be followed up by the âwhatâ or âwhyâ (the referential direct or indirect object of learning) probing questions. Both of these (may) have a further structural and referential aspect. See also #3 and #7.

- Im using flexible responsive interview technique, within some of this EIT context. Combining EIT with responsive flexible interviewing may not be able to be justified (tbc). Carrying out the interview in a strongly empathetic way, moving at the pace of the interviewee to mutually uncover reflections about their experience. These can manifest in a completely emergent way, or be gently prompted by the interviewer, for broad delimited aspects of the activity (this being based on a pragmatic systems thinking approach to a smart learning activity). These aspect reflections are both âstructural aspectsâ (âhowâ and âwhatâ, activity descriptions) and the âreferential aspectâ (the âwhatâ and âwhyâ of learning and experience). - Ashworth & Lucas (2000) especially stress the importance of empathy to support bracketing.

- I can support bracketing in responsive interviews using Rubin & Rubin (2012).

- Delimiting elements of the phenomenon of investigation â the smart learning activity â may now be more able to be argued, because Iâm examining experience of an actual event with these (delimited) aspects in it, with conceptions of the phenomenon in general appearing as a consequence of having participated in this past event. I then probe the variation of experience in these âhypotheticalâ conceptions of aspects of the smart learning activity, in addition to the delimited aspects of the event itself. - Are the delimited elements structural delimitations only, not referential? Would this adversely affect structure of awareness interpretations? No, they are not only structural: a participant may regard some aspects of their experience as âtechnologicalâ (for example) when no direct relationship to technology seems âobviousâ. Likewise, interpretations about âplaceâ (again, for example) may involve access to technologies, or interactions with peers or other persons. The lines between delimited elements and how they might âworkâ in experience awareness are blurred and involve meaning as well as structure.

- A (key) basis for these delimitations of the phenomenon is my own background as a researcher and practitioner within user experience, usability and website evaluation projects. I, as the researcher, have an âassumed knowledge of the phenomenonâ to attempt to âidentify critical aspects of the phenomenonâ (Edwards, 2005, p. 100). Edwards uses introductory questionnaires and probed interview techniques.

- Trigwell (2000, and 1994) is a basis for precedent of interview âsectionsâ in phenomenography.

- Other phenomenographers who argue in favour of specifics of interview topic or researcher âinputâ, e.g. Roisko, 2007, pp 121-123, Ashworth & Lucas, 2000, p. 299, Berglund, 2005, p. 35, Koole, 2011.

- Use EIT as part of the justification for âdrilling downâ aspects of the past event. This may be appropriate as part of the developmental nature of the phenomenography, in this case, for learning design ârequirementsâ.

- The âsystemâ of a smart learning activity implicit in work such as Spectorâs (2014) as a basis for how interview is structured and then analysed iteratively at collective level.

- May also use Dron, J. (2018) to back up a smart learning environmentâs âconstituent parts, including those of its human inhabitants and the artefacts and structures they wittingly or unwittingly createâ.

- Correlating Bloomâs and Solo in relation to phenomenography is also a consideration (for any learner generated content in the smart learning activity). This has been done previously in phenomenography, by Newton & Martin (2013).

- Hitchcock (2006) can be used to justify combining methodologies and to build justification for the idea of different data analysis, highlighting Ă kerlind (2005a) especially, from Hitchcockâs perspective.

- After reading Harris (2011), I realise that clarification of how I interpret the internal and external horizon in relation to theme, thematic field and margin of Marton (2000), after Gurwitsch (2010) is key. Harris (2011) lists 36 studies showing variations of this. Interestingly, she lists Sylvia Edwards (2005), on whose study I have built my own, as challenging Copeâs 2004 interpretation. My own assertion will be that these concur, Edwards only acknowledging the blurred line between internal/external horizon and theme, thematic field to margin. - I will use S. Edwardsâ (2005) and Cope (2004) to create scales after Copeâs table model.

- I need to clarify how I will code â using open in vivo coding as much as possible for first layer, moving to an open axial style second layer? etc. Cosham (2017) and A Edwards (2011) may help with this.

- An aspect fundamental to the study is to clarify what âeffectiveâ learning is. I have considered this in a variety of ways. I believe, as pragmatism is at the heart of any pedagogical guide to smart learning I may formulate, that the way I need to interpret effectiveness of learning is in relation to smart learning literature, not any notion of assessment or graded measurement. Rather, to use Liu et alâs (2017) benchmark statement about âlearning to learning, learning to do and learning to self realisationâ for how smart learning aims to embrace a holistic concept of learning, for the learning city and lifelong learning in all forms. - In other words, effective smart learning environments may be considered as: âenhancing independent learning in an environment of discovery and collaboration, building knowledge for skills, techniques and problem solving in an engaged connected participation.â This statement could be said to be the aim of the outcome of the thesis. This meets Beethamâs model of networked learning activities head on, bringing it up to date for hybrid places and spaces enhanced both by technology and activity design. This is an aim of the thesis, to find empirical evidence for this statement, and is the essence of question 3.

- Work relating to this view of effective learning found in: - Dron, J. (2018).

- Gros, B. (2016).

- Hwang, J-G. (2014).

- Spector, J. (2014).

- To posit: âby situating the learner in places and challenges that create scenarios of natural engagement and discovery (physical, imaginative, creative, sensory), learning can occur on multiple levels. The immersive context that the learner is placed in can elicit the smart learning principles of learning to learn, learning to do and learning to self realisation muted by Liu et al (2017).â This is social constructivist, social constructionist and connectivist in nature. Learning design therefore is addressed in these participatory pedagogies, to a greater or lesser degree, for differing purposes and types of learning and learner. This is the essence of question 1, and leads into question 2: Aim to look for and attempt to evidence this stance, using: - data found in prior literature (the meta analysis, for predominant discourse relating to faceted search employed)

- the experience of the learners ranging from - overall structure of awareness conceptions variation

- pedagogical aspects of interest level of presence and complexity - triangulating with LGC using Bloomâs and SOLO scores

- delimited system elements

- micro-pool activity meaning variation

Â

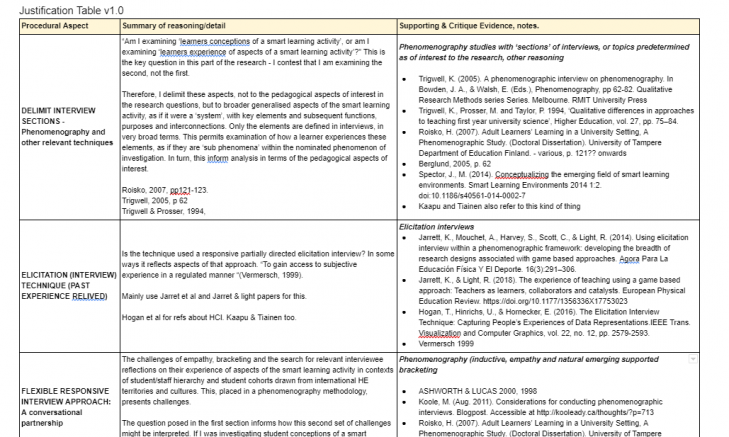

A âTable of Justificationâ

Another way to see this justification is to use a table, to sort out who is justifying what in my whole process. This table is helping me to organise the ideas and argument, a work in progress.

Google Doc table of justification

Key texts I have found that might be able to help me atm: Roisko (2007) thesis, that has clear and fairly indicative argument for the kind of position Im taking, though itâs not âthe sameâ. Jarett and Light do some (I think) very relevant work combining (past tense) EIT and phenomenographic analysis.Â

Connections between methodology, method, process and research questions

It is imperative to clearly indicate the relationship(s) between chosen methodologies, methods and process and the research questions. The audit of the process must show why and how it relates to the questions, and how the questions have defined the process, within a context of theory and existing practice precedent.

- Can we formulate an effective pedagogy for smart learning using Connectivism as a foundation?

- How does this pedagogical framework inform the design of smart learning?

- How can we measure the effectiveness of smart learning involving both assessment of learning (content) and assessment for learning (process)?

Question three in a sense defines the project and is in a sense the first question, as without resolving this, the other two questions cannot be resolved. Itâs essence is noted in #8 above. As a consequence of #8, we can then attempt to define the parameters of a pedagogical framework, or some semblance of it, in #9. By then looking at and defining (evidencing) #9, we are able to answer question one. Question two follows closely after, being aligned to how question one is resolved.

Footnotes

- Some type of analysis is needed to delimit element structure of awareness. Perhaps use level of presence and complexity, as would be used in pedagogical aspects of interest iteration. First iteration anticipated to be a structure of awareness derived from meaning found in any aspect of interviewee transcripts, this could be âcreativityâ, âweatherâ, âfriendsâ etc (i.e. not (only) derived from delimited elements). This meaning then analysed according to Edwards/Cope interpetations of internal and external horizon. This is all ongoing work.

Sources referred to in this text:

- Ă kerlind, G. (2005a). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research and Development, 24, 321â334.

- Ă kerlind, G. (2005b). Learning about phenomenography: Interviewing, data analysis and the qualitative research paradigm. In Bowden, J., & Green, P. (Eds.), Doing Developmental Phenomenography, pp 63-73. Qualitative Research Methods Series. Melbourne RMIT University Press.

- Ashworth, P., & Lucas, U. (2000). Achieving Empathy and Engagement: A practical approach to the design, conduct and reporting of phenomenographic research. Studies in Higher Education, 25:3, 295-308. DOI: 10.1080/713696153

- Beetham, H. (2012). Designing for Active Learning in Technology-Rich Contexts. In Beetham, H., & Sharpe, R. (Eds.), Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing for 21st Century Learning (2nd Ed) (pp 31-48). New York and London. Routledge. Taylor & Francis.

- Berglund, A. (2005): Learning computer systems in a distributed project course, Doctoral Dissertation, Uppsala University, Sweden.

- Cope, C. (2004). Ensuring Validity and Reliability in Phenomenographic Research Using the Analytical Framework of a Structure of Awareness. Qualitative Research Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2004: 5-18. Retrieved from http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=133094720910488;res=IELHSS

- Cossham, A, F. (2017). An evaluation of phenomenography. Library and Information Research Volume 41 Number 125 2017

- Dron, J. (2018). Smart learning environments, and not so smart learning environments: a systems view. Smart Learning Environments 2018 5:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-018-0075-9

- Edwards, A., W. (2011). Using example generation to explore undergraduatesâ conceptions of real sequences: A phenomenographic study. (Doctoral Dissertation.) Retrieved from https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/8457

- Edwards, S. (2005). Panning for Gold: Influencing the experience of web-based information searching. (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16168/

- Gurwitsch, A. (2010). The Collected Works of Aron Gurwitsch (1901-1973), Volume III. The Field of Consciousness, Theme, Thematic Field, and Margin. Richard M. Zaner (Eds.). Springer

- Harris, L., R. (2011). Phenomenographic perspectives on the structure of conceptions: The origins, purposes, strengths, and limitations of the what/how and referential/structural frameworks. Educational Research Review 6 (2011) 109â124.

- Hitchcock, L. (2006). Methodology in computing education research: a focus on experiences. 19th Annual Conference of the National Advisory Committee on Computing Qualifications (NACCQ 2006), Wellington, New Zealand. Samuel Mann and Noel Bridgeman (Eds).

- Hogan, T., Hinrichs, U., & Hornecker, E. (2016). The Elicitation Interview Technique: Capturing Peopleâs Experiences of Data Representations.IEEE Trans. Visualization and Computer Graphics, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 2579-2593.

- Hwang, J-G. (2014). Definition, framework and research issues of smart learning environments â a context-aware ubiquitous learning perspective. Smart Learn. Environ. 1, 4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-014-0004-5

- Jarrett, K., & Light, R. (2018). The experience of teaching using a game based approach: Teachers as learners, collaborators and catalysts. European Physical Education Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17753023

- Jarrett, K., Mouchet, A., Harvey, S., Scott, C., & Light, R. (2014). Using elicitation interview within a phenomenographic framework: developing the breadth of research designs associated with game based approaches. Agora Para La EducaciĂłn FĂsica Y El Deporte. 16(3):291â306.

- Koole, M. (Aug. 2011). Considerations for conducting phenomenographic interviews. Blogpost. Accessible at http://kooleady.ca/thoughts/?p=713

- Liu D., Huang, R., & Wosinski, M. (2017). Future Trends in Smart Learning: Chinese Perspective. In: Smart Learning in Smart Cities. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. Springer, Singapore.

- Marton, F. (2000). The structure of awareness. In Bowden, J. A., & Walsh, E. (Eds.), Phenomenography, pp 102-116. Qualitative Research Methods series Series. Melbourne. RMIT University Press

- Newton, G., & Martin, E. (2013). Blooming, SOLO Taxonomy, and Phenomenography as Assessment Strategies in Undergraduate Science Education. Journal of College Science Teaching, Vol. 43, No. 2 (November/December 2013), pp. 78-90. National Science Teachers Association. Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43631075

- Roisko, H. (2007). Adult Learnersâ Learning in a University Setting, A Phenomenographic Study. (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Tampere Department of Education Finland.

- Trigwell, K. (2000). A phenomenographic interview on phenomenography. In Bowden, J. A., & Walsh, E. (Eds.), Phenomenography, pp 62-82. Qualitative Research Methods series Series. Melbourne. RMIT University Press

- Rubin H., J., & Rubin, I., S. (2012) Qualitative Interviewing, The Art of hearing Data. 3rd Ed. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC. Sage Publications.

- SÀljö, R. (1979). Learning About Learning. Higher Education 8 (1979) 443-451, Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam

- Spector, J., M. (2014). Conceptualizing the emerging field of smart learning environments. Smart Learning Environments 2014 1:2. doi:10.1186/s40561-014-0002-7

[pdf]